Polynesia Tatau Festival was held last spring. Moving into the heart of the Pacific Ocean has allowed us to put into perspective the geographic and cultural features of this particular territory, this island, traditional cradle of contemporary tattoo. This was also an opportunity to discover some fifty local and international artists through the sharing of their knowledge and the exchange of their cultures. Report.

Five years since the Polynesia Tatau Association, chaired by Laurent Purotu, organizes this festival in Tahiti, resolutely rooted in its territory. We are in the heart of the Society Islands, which with Tuamotu, Gambier, the Austral and Marquesas Islands, shape French Polynesia. A total of 118 islands located about 6,000 km from Australia, forming a surface area as large as Western Europe. A unique area, perfectly represented by the chosen venue for the festival: Botanical Gardens of Tahiti et des Îles Museum, located in Punaauia, on the Pointe-des-Pêcheurs, 15 km from Papeete. This lush tropical vegetation overlooking the turquoise lagoon in the Nuuroa pass and facing Moorea offers a postcard view. It also reveals the essence of Polynesia: an area where the sea prevails on earth, where the sea connects lands.

Even though Polynesian tattoo is rooted in the heart of the cultural development of its metropolis, Polynesia still projects (too much) the image of Gauguin, Matisse, Jacques Brel, commercials by white sandy shores and welcoming "vahinés", a haven for tourists in search of sun and ultramarine blue. Supported by the Ministry of Culture and the Centre des métiers d'Arts of Tahiti, the festival highlights a whole different angle of culture. Out with tourist clichés that are blurring the way we look at this place. It's time to embrace Polynesian history and culture as it is today; produced, written and lived by Polynesians themselves. With this in mind, the festival gives pride and revives the plurality of traditional Polynesian customs through demonstrations: Pahu (drum; symbol of Marquesan culture), Haka (renowned Maori dance, still performed throughout Polynesia), ’Õrero (art of speaking to capture the attention of an audience), Kava ceremony (traditional Melanesian drink made from shrub roots), Monoi preparation (from Tiaré flower, symbol of Tahiti) or making of Horo (women's fragrant headdress made out of plants). All under the aegis of "Te Ahi – Fire", the Umu-ti ceremony masterfully revealed what was also the theme of the festival. Orchestrated by the tahua (priest) Raymond Graffe, this walk on red-hot stones to purify the body and mind that was a crucial ritual in the Polynesian cosmogony, is now transmuted into a real community experience, a return to roots and to Gods.

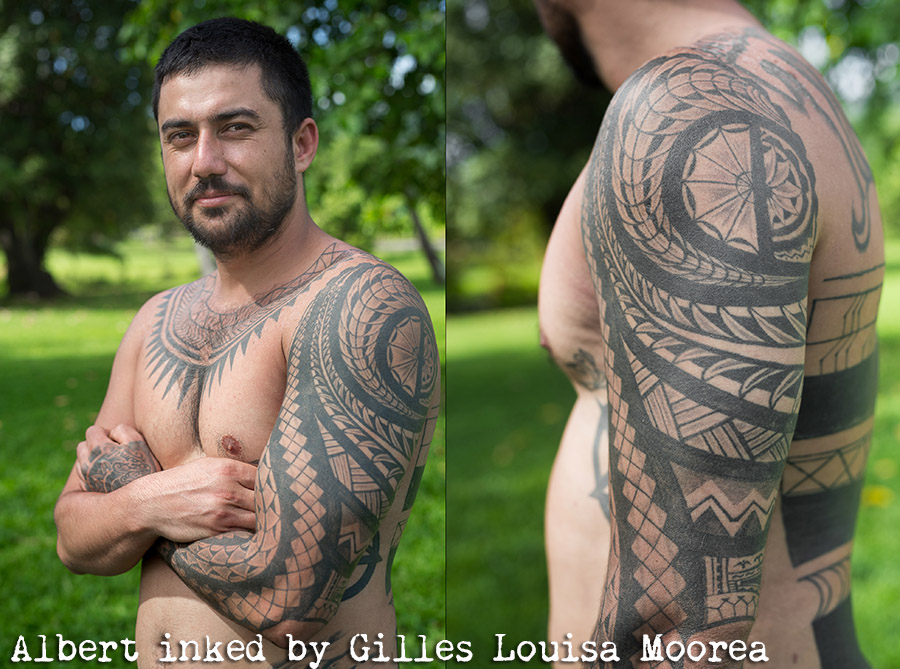

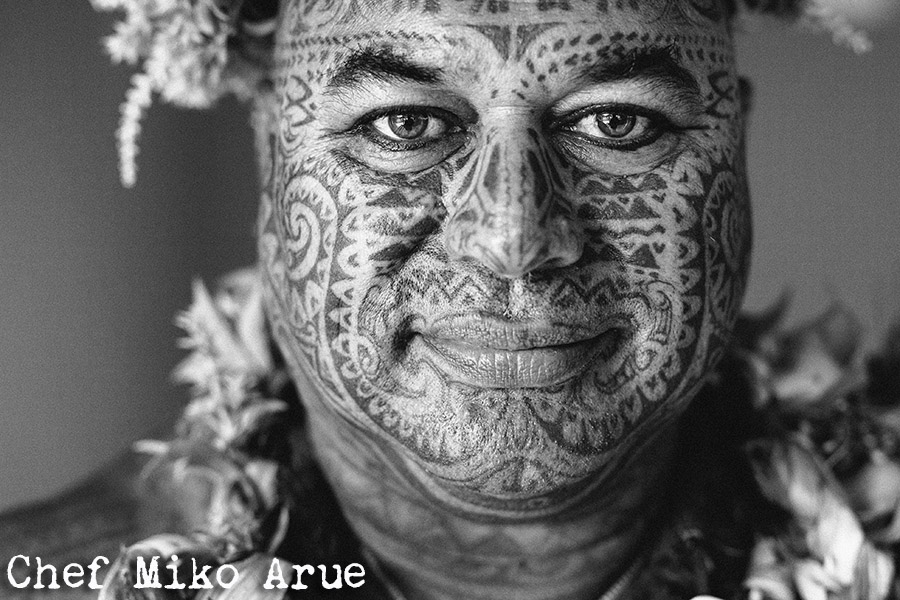

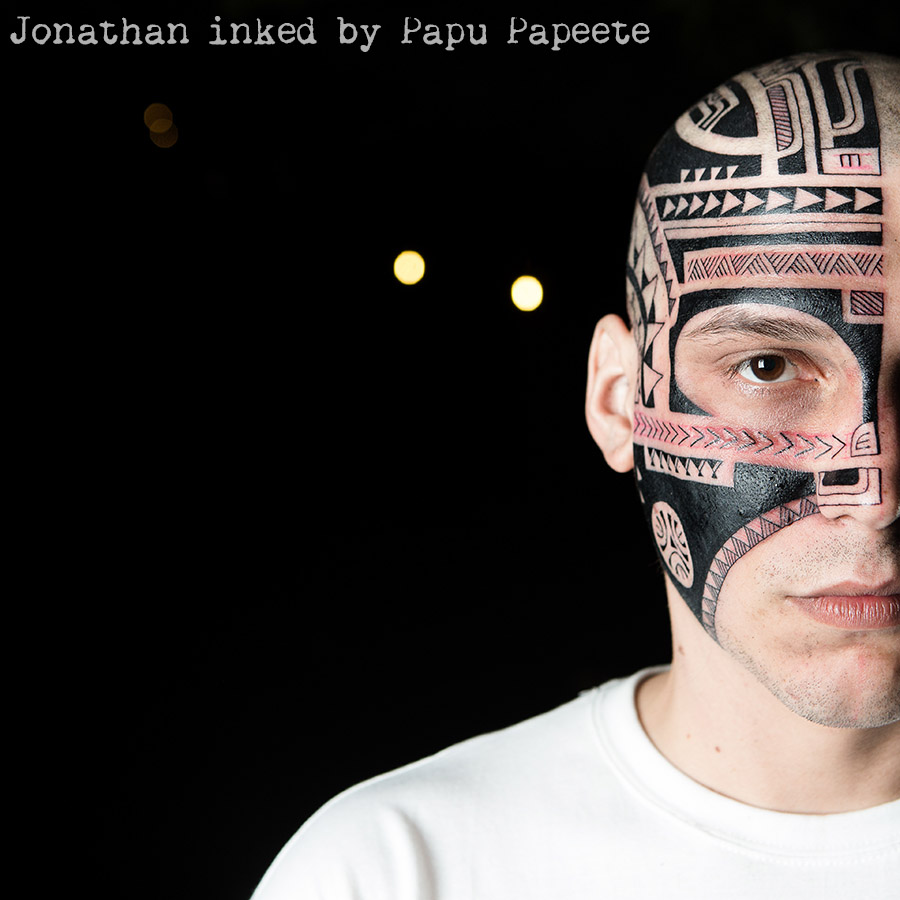

Within the building of a common language on the convention side, sixty tattoo artists had been invited. Most of them were from the islands, and fifteen had came all the way from Japan, Australia, Canada and Chile. Japanese, tribal and realistic designs rubbed shoulders with the most ancient iconography, and rotary and coils worked alongside with combs and teboris. The purpose of this melting pot? To promote contemporary tattoo in all its forms, while recognizing the special place held by Polynesian tattoo. Forgotten long ago and rediscovered in the early 1970s, it became an international style worn by millions of tattooed people worldwide. This welcomed globalization allowed to broadcast, to reinvent, to hybridize the practice – as all global cultures – but those current arrangements are questioned in Polynesia. While this mass dissemination, through all individual and group research, helped the historicization of tatau, and contributed to the emergence of more effective techniques and iconography, it blurred its sens and value for some. Historical and geographical confusions are indeed numerous, borrowings are endless, scientific bases are shifting ... This complex context otherwise constantly reassessed with globalization, makes it difficult for Polynesian people to assert their culture and identity in this field. Thus, many researchers are reconsidering, sourcing, listing, locating and classifying components of the past of tatau, with the protection of its form and substance in mind. The festival, wishing to open both a local and international window on the matter, had organized a series of lectures on tatau's history, symbolism, aesthetic and evolution.

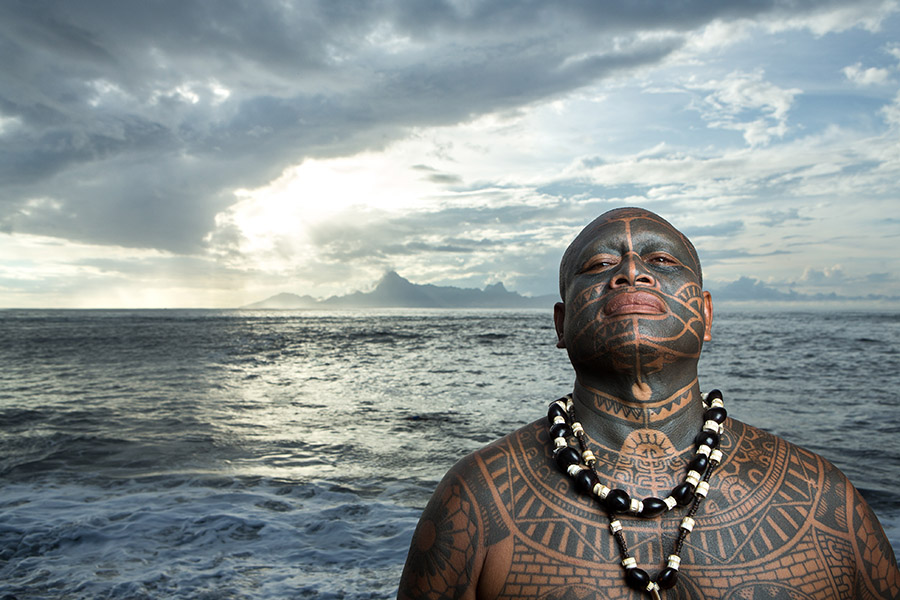

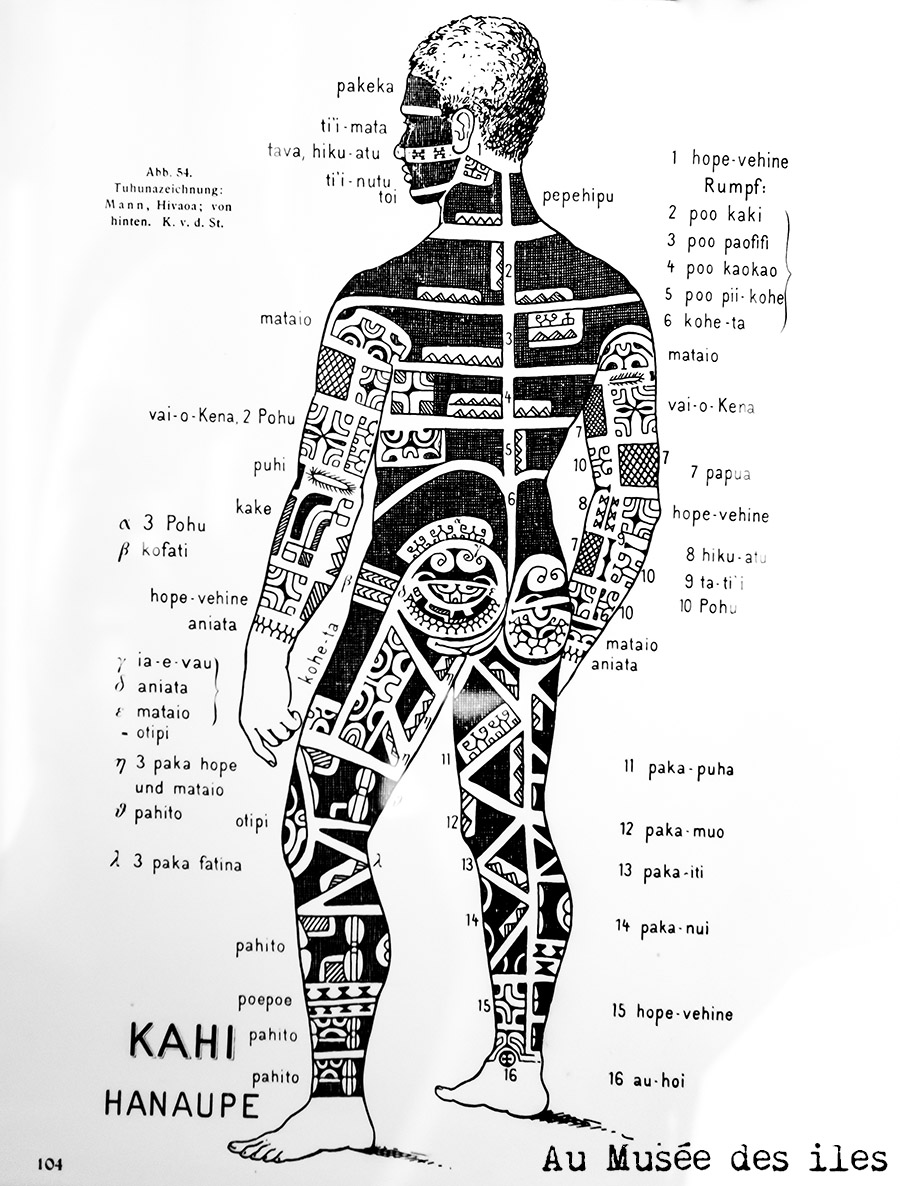

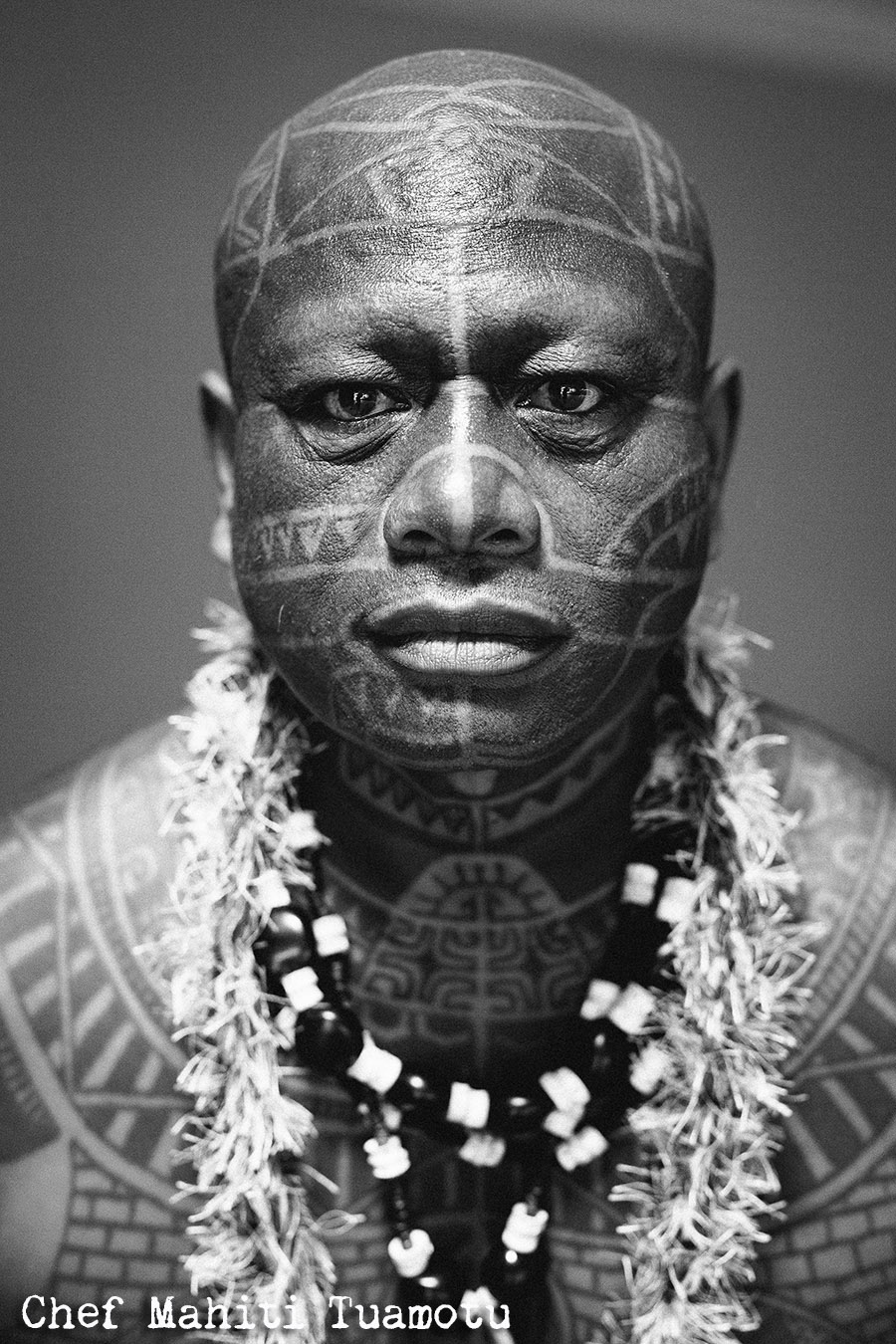

Understanding the motives and direction to better reinterpret them, making visitors realize that the words "Polynesian tattoo" and "Tatau" are certainly convenient qualifiers, but their inclusiveness does not reflect the diversity of forms and techniques involved. Indeed, in each archipelago, styles and practices were revealed by the diversity of patterns and symbols scattered in every booth and through every artist's origin. Cosmopolitanism also readable in a semantic way: if in Marquesas, the word for tattoo is Patutiki, in Tahitian, it's called Tatau Tahiti, in New Zealand, it's Tamoko and in Samoa Islands, the word is Ta Tatau Samoa. This individuation of words shows the effort made by institutions and communities to protect and sustain local cultures. However, this development that focuses on differentiation should not be seen as withdrawal. It is rather the principle to "assimilate without being assimilated,” resting on the desire to preserve a unique culture, namely mana, this emanation of spiritual power of the group that contributes to the gathering, which is the most beautiful allegory. The purpose in mind is to enable people to understand the designs and their meanings to better reinterpret them, both stylistically and/or symbolically. This represents one way for Polynesian tattoo to reinvent itself while respecting its unique history, a sign of its constant adaptability according to times, and a demonstration of its unique artistic vitality. For more information: Facebook: @PolynesiaTatauTattooConvention

Sidebar: Polynesian Cultural Revival This cultural revival that covers all Polynesia (and broader Oceania) since the 1970s and 1980s, is illustrated by the need to find practical roots that were mostly banned in the late 18th century, during the Christianization of various archipelagos and their annexation, to later be placed under colonial protectorate in the 19th century. While evangelization in Polynesia had the corollary to discourage practices it considered "pagan,” "obscene" and "savage,” what had "survived" could not resist the new political, religious and social systems set up by the metropolitan government. In other words, with forced changes in politics, culture and traditional rituals performed by settlers, Polynesian beliefs, customs and traditions gradually lost their meaning, accelerating their disappearance. Tattoo was no exception. The colony becoming a territory, a community and finally an overseas country allowed Polynesia to have its own specific institutions. Concomitantly, it started a valorization process of landscapes, languages, local knowledge and traditional practices, through the restoration, reclaiming and rehabilitating of songs, dances, sculptures, crafts and tattoos that are unique to each island or community. This patrimonialization of the past also responds to purposes other than the will to perpetuate what was forgotten or mythologized. Indeed, beyond promoting what matters to current generations, is the building of personal and collective identities and their inclusion as part of a national Polynesia unity, differentiated, but united, which is currently taking place.

Sidebar: Polynesian tattoo is a phoenix; several factors enabled the revival of Polynesian tattoo practice. First, its persistence in some Pacific Island locations, including Samoa, located about 2,600 km from Tahiti. Aware of being one of the last guardians of knowledge lost in its vast majority, the independent territory, in the late 1970s, became a rediscovery and dissemination center for traditional practices, by the growing interest it inspired among Polynesian tattoo artists (in 1982, Tavana Salmon went to Samoa and returned to Tahiti accompanied by a tattoo artist and his assistant); but also to European and North American tattoo artists, who saw the study of forms and traditional methods as a way to enrich their imagination and their techniques. We think of Leo Zulueta, Ed Hardy, Henk Schiffmacher, Cliff Raven, Dan Thomé or Lyle Tuttle, one of the first to get a tattoo in Samoa in 1972. These individual initiatives created a style, the "new tribalism,” which once published in magazines of the time, triggered the public's enthusiasm and contributed to its popularization. Meanwhile, Polynesian tattoo artists are documenting themselves. "L'art du tatouage aux îles Marquises" of German author Karl von Steinen, also author of a catalog consisting of nearly 400 tattoo patterns based on research through drawings by Marquesan tattoo artists in the 19th century. They also travel, particularly during international conventions in Europe and the US, to which the organization of Polynesian tattoo festivals and conventions responds in late 90s. With ever-increasing exchanges between Western and Polynesian tattoo artists, the practice has enriched and diversified itself, based on origins (Marquesan, Tahitian, Maori, etc.) in which it is rooted and from which it is inspired.

Polynesia Tatau Festival - Tattoo, Polynesian Cultural History Text : JWT, Photos: © P-Mod, Translation : Joanie Gélinas