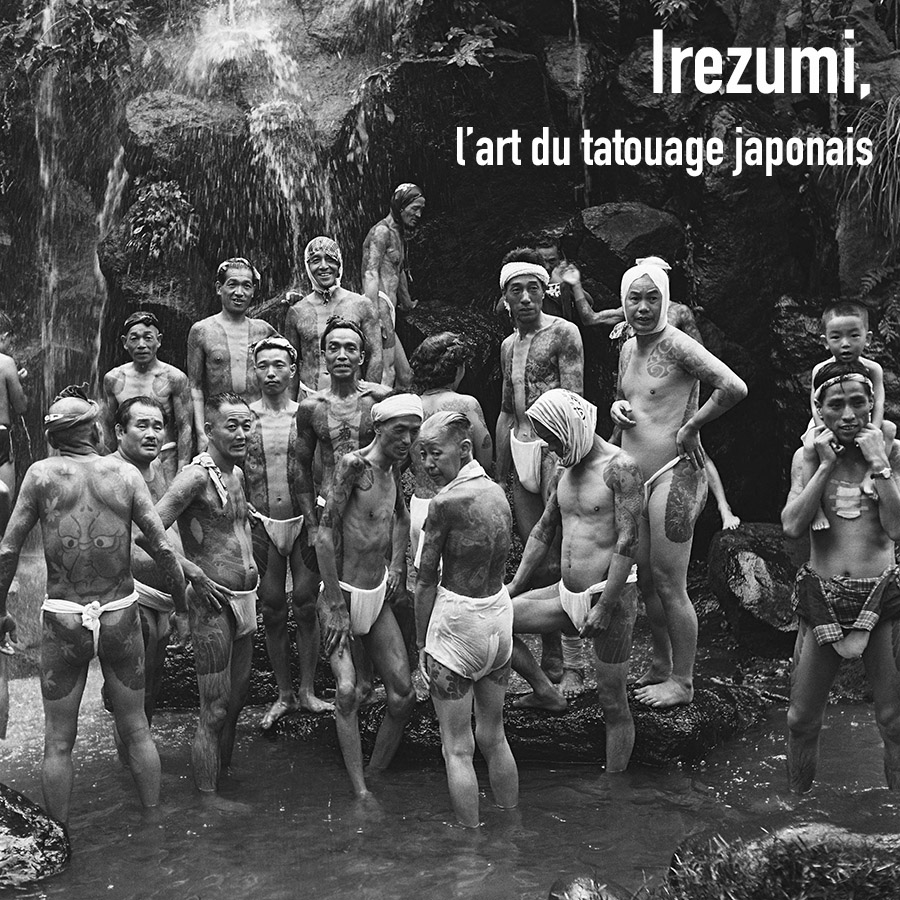

From November 28, 2020 to March 20, 2021 the Écho gallery in Paris paid tribute to the great Japanese tattooing tradition with a collective exhibition entitled: "Irezumi, the art of Japanese tattooing". An event during which enthusiasts were able to discover for the first time the work of Akimitsu Takagi, an unpublished testimony recently rediscovered, on the world of Japanese tattooing in post-war Tokyo.

Five photographers (Achim Duchow, Irina Ionesco, Chloé Jafé, Akimitsu Takagi, Hitomi Watanabe) five points of view of women and men to reflect the complexity of an art, unloved in her country for its association with crime, at the same time as adored in the rest of the world for its beauty and sophistication. A situation on which the news in recent years nevertheless seemed to give encouraging signs of a change in mentalities. After a long freedom to practice lawsuit won in 2020, Japanese tattoo artists have never been so close to official recognition of their activity. When will the tattoo be in Japan?

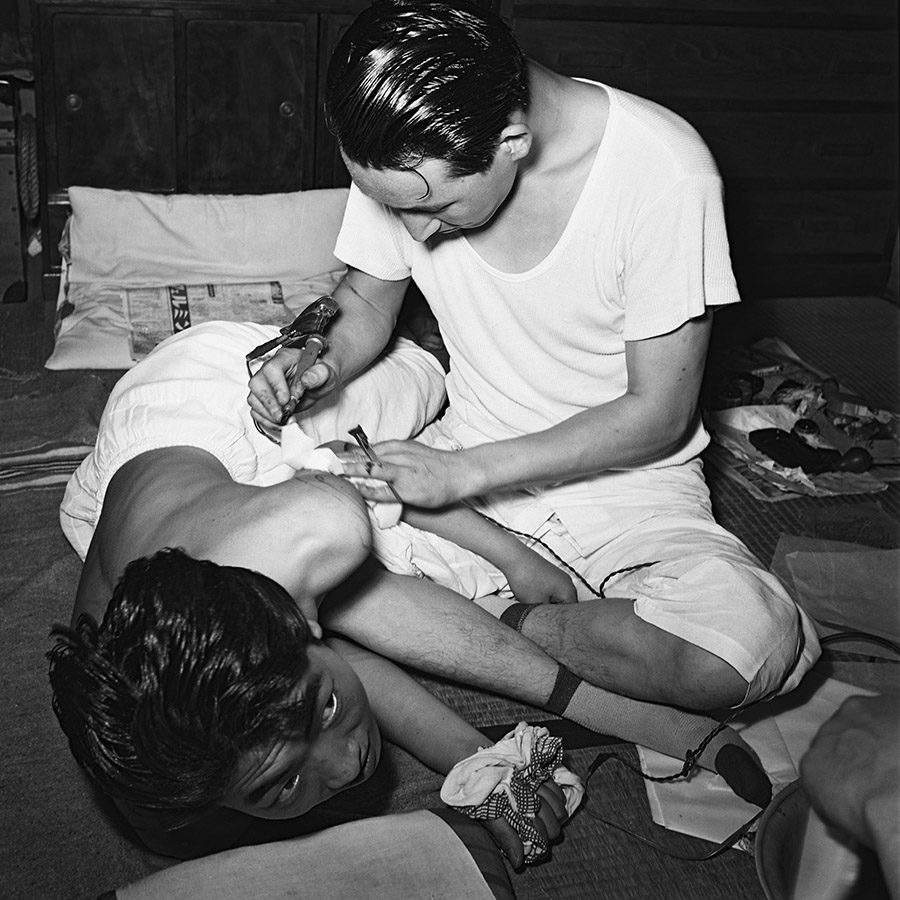

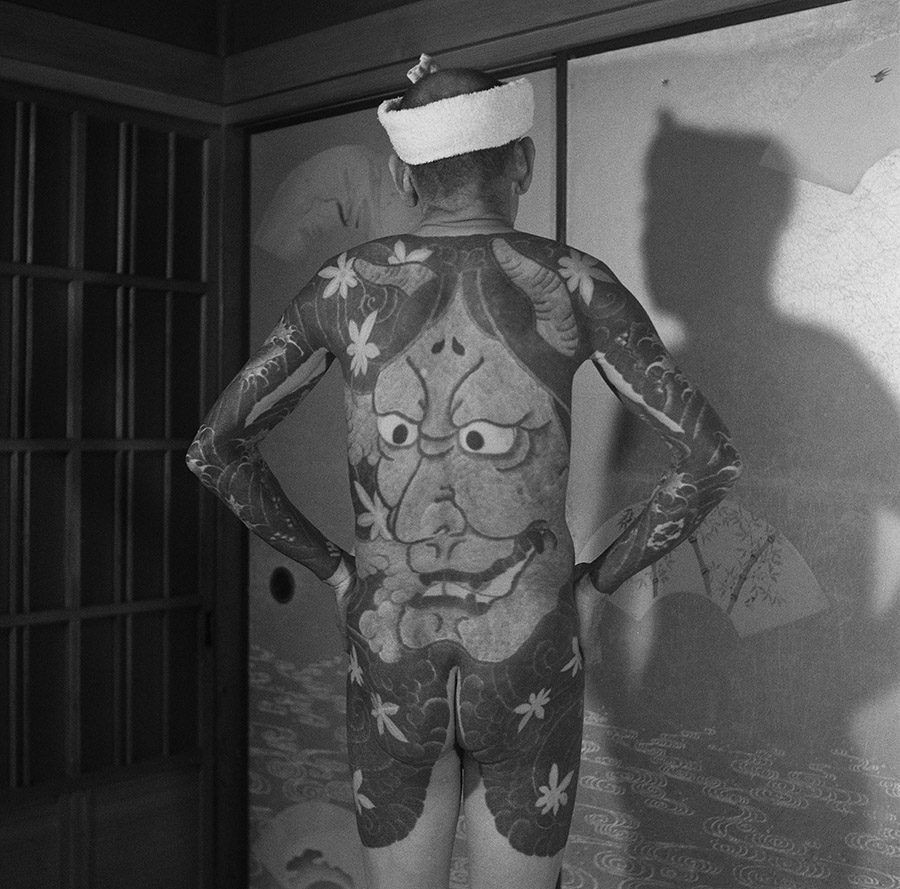

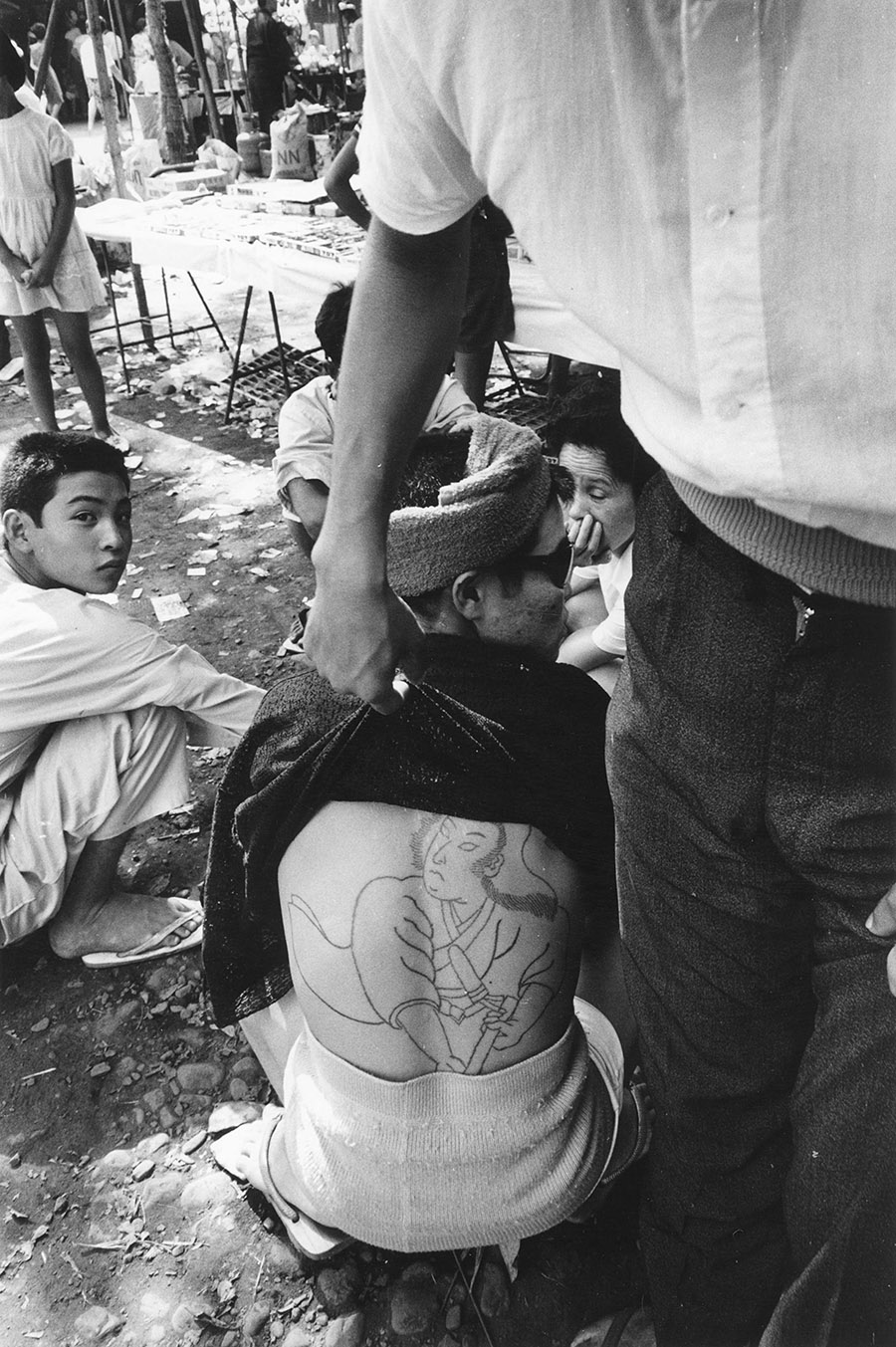

This was the hope of Akimitsu Takagi, one of the photographers featured in the exhibition. Fascinated by it, Takagi, born in Japan in 1920 and died in 1995, very early on denounced the prejudices against traditional Japanese tattooing and raised the need to look at the works of tattoo artists from an artistic outlook. A point of view defended in his books -Takagi is in fact a writer, one of the greatest authors of the 20th century detective novel whose first novel published in 1948 was the subject of a first translation in France under the title Irezumi in 2016– but also in his photographic work, one of his passions, as we discovered here at the Echo gallery. The story is fascinating: Takagi is said to have come into contact with the tattoo community while writing his first novel. Taking advantage of this privileged access in this ultra-confidential environment with which he became familiar, Takagi thus photographed in the years 1950/1960 the greatest tattooists of the time and their clients, taking care at the same time to document their tattoos - thus constituting an archive of the time. An unparalleled testimony known to this part of the history of tattooing in Japan, a treasure forgotten in the library of the Takagi family, recently unearthed by French journalist Pascal Bagot, a specialist in Japanese tattooing. Images - superb, they reveal the photographer behind the writer - taken from an archive of which we would like to see more. But it seems that a book is in the works ... To be continued on the author's Instagram profile (IG: @pascalbagot).

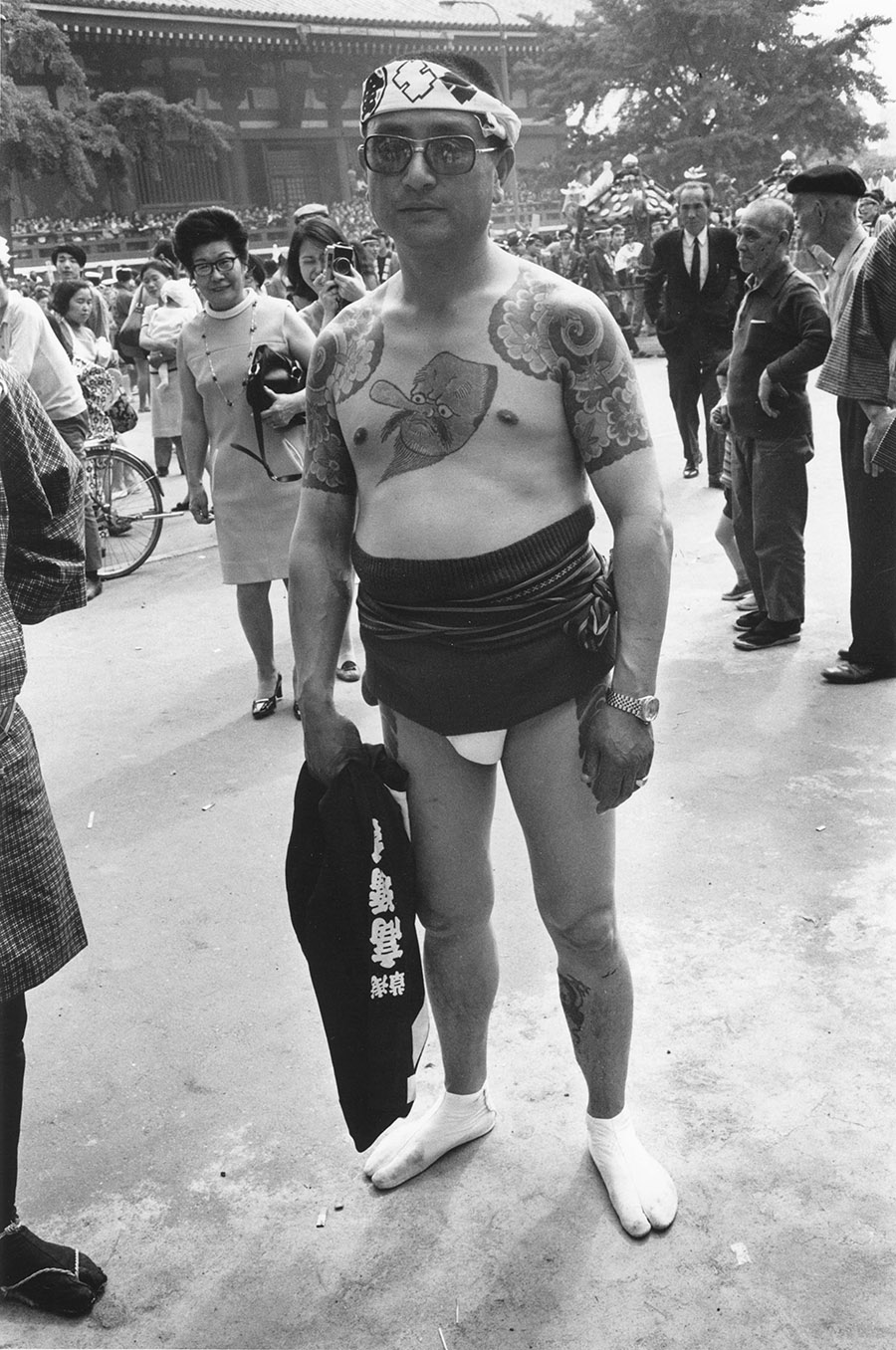

Known for her coverage of the student protests in Tokyo in 1968, Japanese photographer Hitomi Watanabe also took an interest in the tekiya corporation in the late 1960s. She thus followed for three years these men, fairgrounds in a way, whose main activity is to organize itinerant markets, temporarily installed near the temples on the occasion of the many festivals of the Japanese calendar. As the beautiful black and white prints on display showed, they were still tattooed in the days of traditional designs, testifying to the enduring connection that has existed since the 19th century and the Edo period, ancient Tokyo, between popular culture and body decoration when, in the wake of prints and their immense success, craftsmen, carpenters, firefighters, etc., loved to tattoo themselves for taste and pleasure.

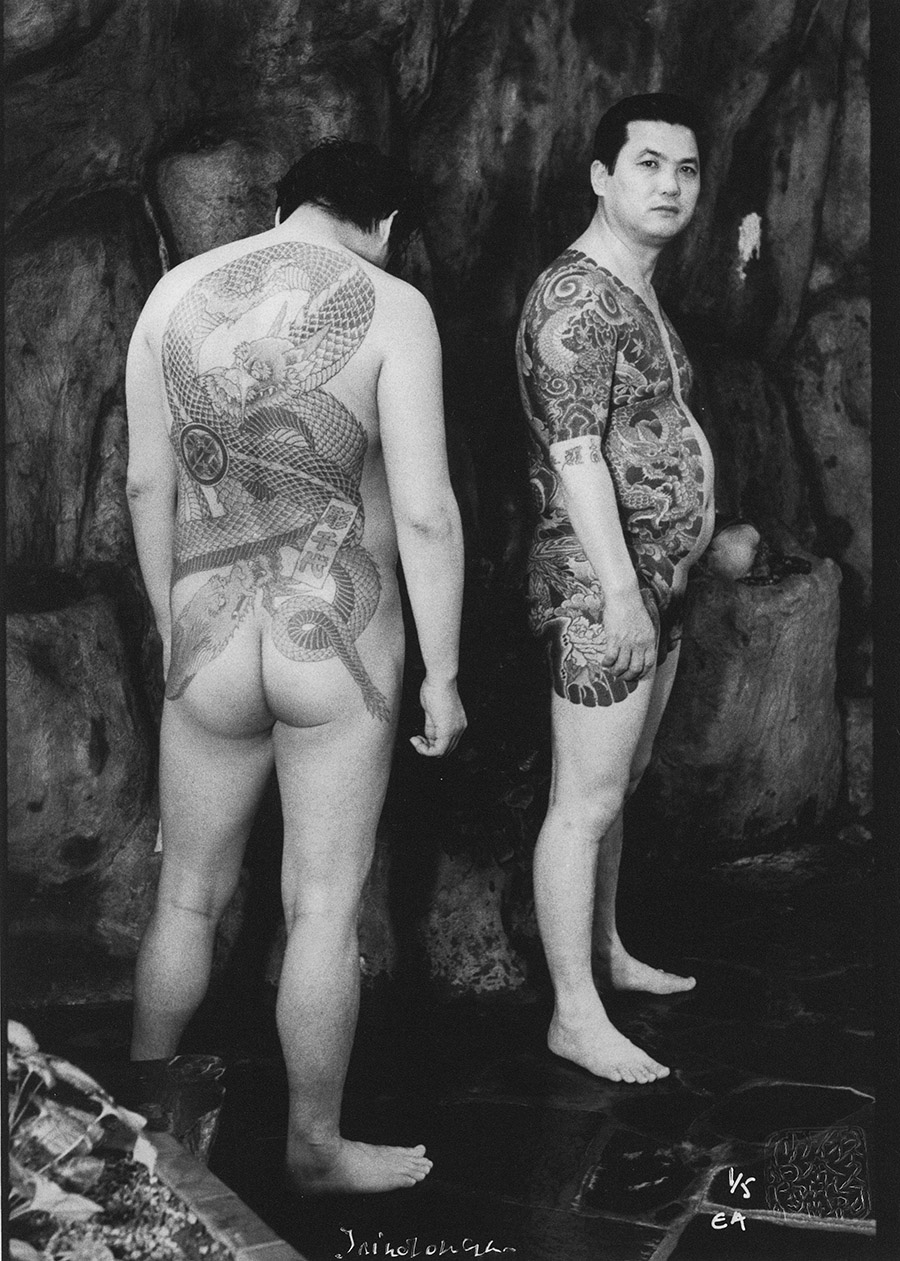

The persistence of this ancient time was also illustrated by the link between tattooing and outlaws, especially the yakuza. Directed by the Frenchwoman - of Romanian origin - Irina Ionesco, the black and white series presented, made in 1996, immortalized the figure of the tattooed bad boy, captured here naked, eroticized in the atmosphere of a Japanese bath, one countless hot springs as there are in the archipelago. These same places which mostly prohibit their access to tattooed people, precisely on the presumption of their belonging to organized crime. A community tradition also shared by women, as Cholé Jafé showed more unexpectedly, the French photographer who for several years pursued in the world of the Japanese underworld a work between photojournalism and author research. - https://www.galerieecho119.com