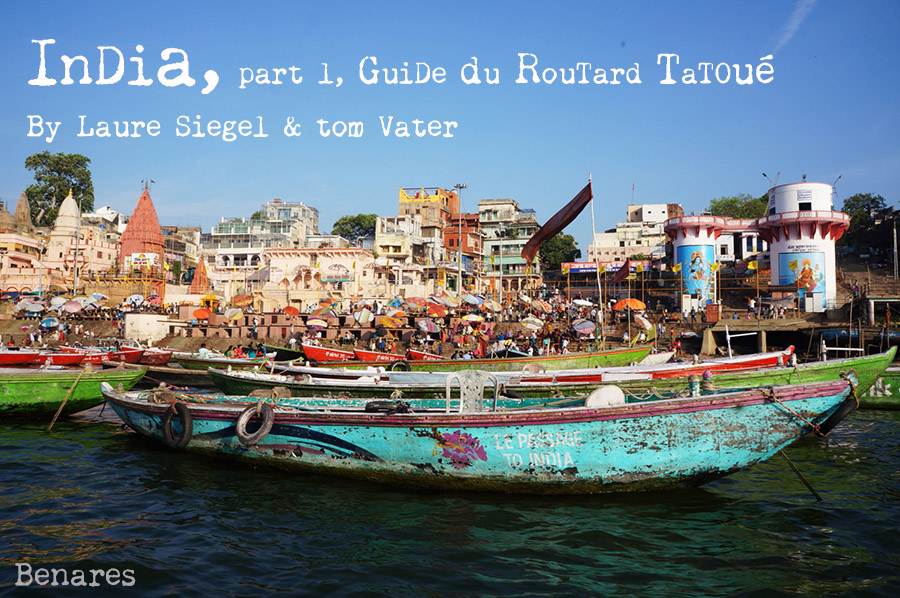

One and a half billion people, hundreds of languages, a multitude of beliefs and religions, climates, geographies, cultures and politics: welcome to the Indian subcontinent, a whirlwind of ideas and colors, flavors and odors and probably the most visually stimulating place in the world. Since the dawn of time, India has been tattooed. We slalom between the street tattooers of the Madurai temple, met with political activists ready to get tattooed the face of their champion, discovered the world's largest tattoo center in an underground car park in New Delhi, paced the markets in eastern India held by proud women wearing facial tattoos, celebrated Ramadan in Mumbai with artists Sameer Patange and Eric Jason D'Souza and documented the beginnings of the Sri Lankan scene in the middle of the jungle. Text and photos : Laure Siegel & Tom Vater

On the Street The vast population of India gets tattooed in the streets for a handful of rupees or during major religious, political or cultural events. However the offer aimed at the wealthy classes has grown in recent years. In big cities such as Mumbai and Pune, young artists are investing in modern shops, while international tattoo conventions attract crowds in Kathmandu, Goa and Delhi. Between these two extremes, the emerging middle class is getting inked in dives that multiply in the basements of shopping malls, a phenomenon which more or less gracefully accompanied the explosion of contemporary tattoo in India.

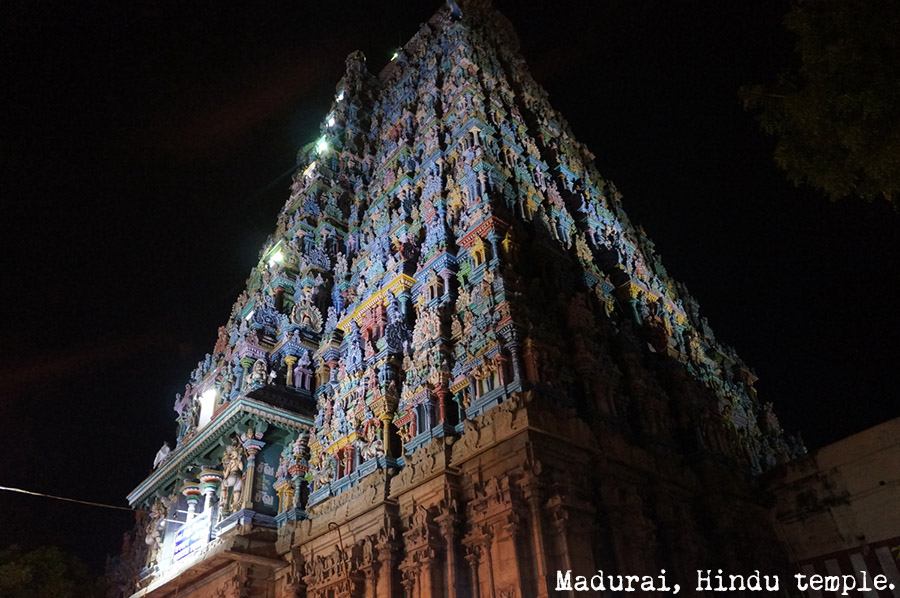

Chapter 1 - The Tattoo Gypsies of Meenakshi Amman Text and photos : Tom Vater Every night, the traffic-free lanes surrounding Madurai's most important Hindu temple, the Meenakshi Amman, a mela, a festive market springs up, catering to thousands of pilgrims. Household goods, Chinese toys, textiles, temple souvenirs, snacks and sweets, and have-your-name-carved-onto-plastic-hearts are sold from countless stalls.

Right in front of the temple’s main gate, a family of itinerant street tattooists has spread crudely hand-carved plastic stamps on the pavement - religious images, tribal patterns, political party emblems and the faces of actors and politicians.

Twenty-something and recently married Navaneetha is here to have the name of his wife, Jothi tattooed on his chest. The bride has come along to lend moral support. Cinemaguru, the head of the family, his brother Jagannath and his cousin Cinemani, have been working pavements around the country for years. Cinemaguru’s sister applies non-permanent henna skin dye patterns to female clients. Several children entertain themselves around the family camp cum office.

Client and artist agree on a price of fifty Rupees and Cinemaguru gets his equipment ready: a crude, unsterilized ink-smeared machine powered by a motorbike battery in a plastic bag. The ink has been purchased from an office supplies shop. Navaneetha doesn’t ask for a fresh needle and Cinemaguru doesn’t offer one.

With a flowery font, he draws Jothi’s name onto Navaneetha’s chest with a pen. Then he raises his needle and begins to attack the young man’s skin. Two minutes into the procedure, and tears drop from his face, as Jothi puts a comforting hand on his shoulder. Dermatologists and tattooists who work in international standard shops bemoan the existence of tattooists like Cinemaguru. The lack of sanitation hugely increases the risk of contracting a number of skin infections along with Hepatitis B, Tetanus and HIV.

Five minutes later, Cinemaguru is done, Navaneetha is ecstatic and the couple happily pay their fee. Cinemaguru applies coconut oil to disinfect the wound and gets ready for his next customer. Most Indians can’t afford to step into a shop with better equipment and hygiene and street tattooists like Cinemaguru will remain in high demand. “My tattoos are popular because I start at twenty Rupees,” he said, “It’s a way for the low wage earners to express themselves.” Text and photos : Laure Siegel & Tom Vater