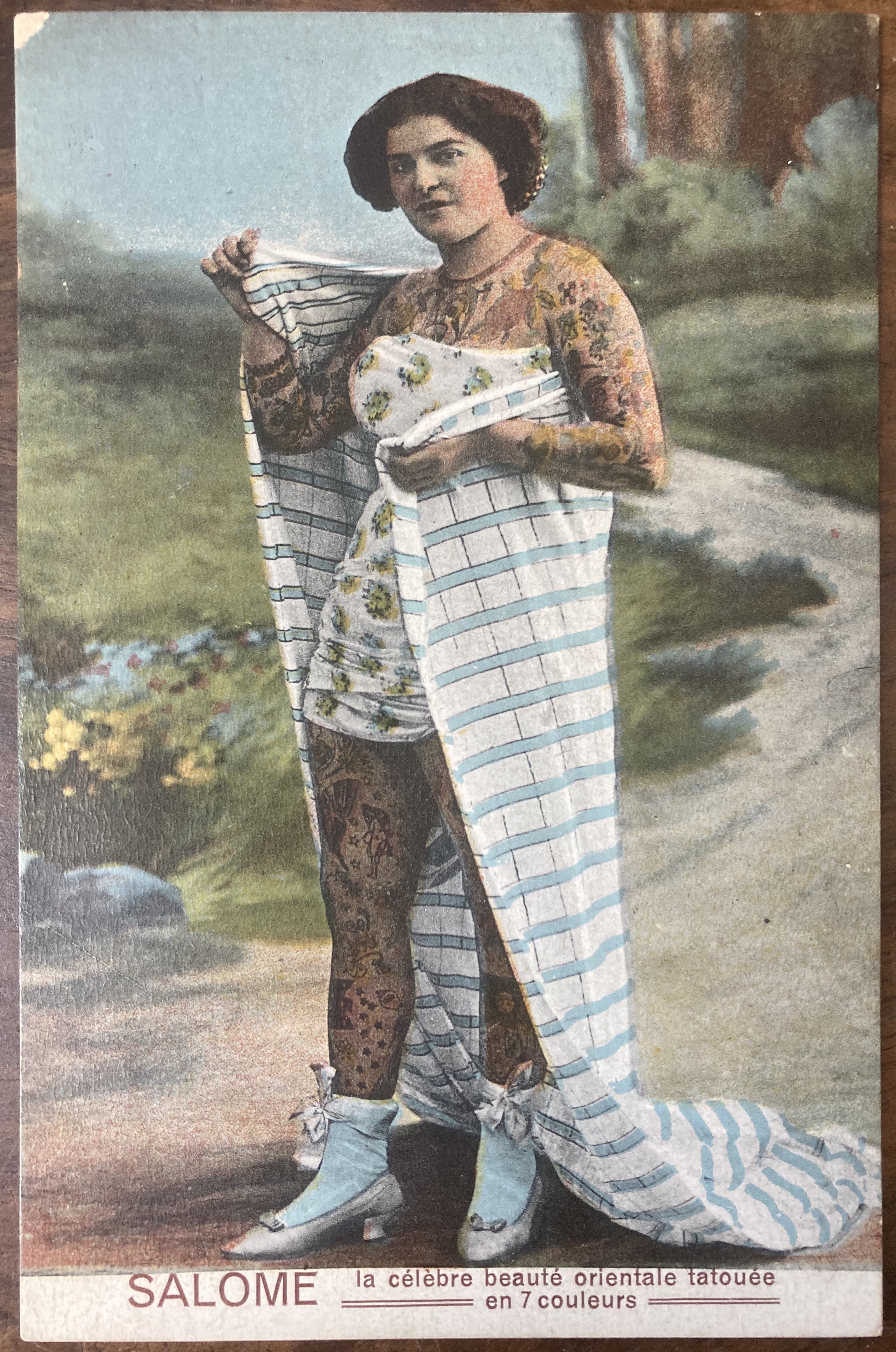

She is well known to all who explore online marketplaces looking for vintage tattoo-related postcards. She is sometimes called ‘Djita’ or ‘Salomé’, or both at the same time; she is tattooed from neck to ankles. ‘Oriental beauty,’ ‘Living multicoloured picture’, ‘Blue woman’… Her image travelled around France, Italy, and Germany at least. Between the 1900s and the interwar period, she became the very archetype of the European ‘tattooed lady’. But what does her spectacular body reveal?

We can see her evolve from picture to picture, aging from her early twenties to her forties. Her tattoos are the only part of her that remains unchanged. They vary greatly in theme: we can see some historical figures (a woman wearing a helmet and holding a spear, an Egyptian woman), references to nature (stars and butterflies, plenty of flowers), some ornaments that might refer to the Middle East. The most noticeable of those ornaments is located on her back: a crescent moon and a star on some sort of flag. Of course, because of technological limitations, the pictures are black-and-white, those some were manually colourised. Their true colours are only perceivable through the postcard’s captions: they speak of seven colours, then eight, then fourteen. Though it might indicate evolution, this obvious self-outbidding might also simply be a commercial strategy aiming at piquing a potential spectator’s curiosity… Those postcards were indeed meant to promote a real-life show. By the time they came to be, the golden age when tattooed phenomenons showed their bodily marks in the greatest Parisians halls was already long gone. They still existed and performed in humbler venues, though, most notably fairs and funfairs. In the early 1910s, we know that Djita Salomé displayed her tattoos in Edinburgh’s Waverley Market (December 1911), in Toulouse’s ‘Théâtre des Nouveautés’ (November 1913), at Laval’s place de l’Hôtel de Ville (April 1914), in Paris’s Bal Tabarin (May 1914)… Her shows were announced through the press and through roughly printed flyers. The postcards served a very specific purpose: they were meant to lay the groundwork for her upcoming arrival. ‘Opposite, the tattooed lady’ wrote someone in a postcard sent from Versailles in 1914. There was no further information about her in this specific letter. But the purpose of the picture was to make her image circulate and amaze, introducing her to the knowledge of her future spectators. They would later recognise her and want to see her.

The postcards also served as a prelude to the show: they showed what each representation was going to revolve around. The captions either give technical aspects of her tattoos (‘(1000,000,000 of punctures). Electric process’) or hint at a wider story (‘A work of art in 14 tones created by the Red Skins of Dakota (U.S.)’). This type of show both revolved around the exhibition of the body and the story told to frame it. The tattoos could either be explained by the tattooed person directly, or by another individual. Maybe Djita Salomé’s show was sometimes centred around the technical side of her tattoos. Maybe it was sometimes included into a wider story of being kidnapped by savages and forced to be tattooed, similarly to la Belle Irène. Djita, the oriental drawings on her body… Something is sure: her success relied on the popularity of Orientalism. In France, Orientalism was brought on by the translation of One Thousand and One Nights in 1704. It culminated in the 19th and the early 20th centuries, due mainly to colonisation. It revolved around the notion of otherness, through stereotypical portrayals of exotic and erotic oriental women. Our tattooed lady’s persona was inspired by the biblical Salomé, who danced for John the Baptist’s head. In 1874, Gustave Moreau depicted her in an unfinished painting where the oriental décor overflows on her bodies in a multitude of tattoos. In the early 20th century, Salomé became the archetype of the ‘femme fatale’ and appeared in several plays and ballets. Our own tattooed Salomé was therefore an immediately identifiable ‘oriental beauty’: she embodied a mysterious, foreign world, both in space and time.

But where did she come from? This is where it gets mysterious. Her real identity remains unknown. We do know that she was represented by a British impresario in the early 1910s: Cornelio, whose address in Oldham, England, is printed on the back of some postcards. Was she British? It would explain the approximative French of some postcard captions. Maybe she was German: most of the cards were printed in Magdeburg. An Italian version of one of the postcards calls her Egyptian: this explanation would make sense. In Djita Salomé’s time, the Egyptian flag depicted three crescent moons and three stars. Maybe the tattoo on her back was a simplified version of her birth flag? Due to the long-lasting influence of Britain over Egypt, it would explain her link with a British impresario.

Djita Salomé remains a mystery. When it comes to her, there are more questions than answers. But she exemplifies a type of showbusiness, and some of the commercial strategies involved in it. Her real identity remains hidden, lost in history. But is it important, really? She fascinated in her time, and she keeps on fascinating today. Sources « Carnival », The Scotsman, 20 décembre 1911. « Au Théâtre des Nouveautés », Le Cri de Toulouse, 29 novembre 1913. « La Belle Djita », Le progrès de la Côte d’Or, 11 janvier 1914. « Sur la place », L’avenir de la Mayenne, 5 avril 1914. « Au Bal Tabarin », Le Journal, 2 mai 1914. « Foire de la Saint-Jean », Courrier de Saône-et-Loire, 26 juin 1914. Sources des illustrations « Salomé. La célèbre beauté orientale tatouée en 7 couleurs », C. O. M., carte postale non circulée (collection personnelle). « Djita (Salomé). Beauté Orientale tatouée en 14 couleurs différents – (100,000,000 de piqûres). Procédé Electrique – », C. O. M., carte postale non circulée (collection personnelle). Gustave Moreau, Salomé tatouée, vers 1874, Musée Gustave Moreau (Wikimedia – Domaine public). « Djita. Bellezza Egiziana. Tatuata in 14 differenti colori. 100.000.000 di punture. Processo Elettrico », carte postale non circulée (collection personnelle). Pour aller plus loin Alexandra Bay, « Djita Salomé, princesse orientale tatouée », Tattow Stories, 2018. Jane Caplan (dir.), Written on the Body. The Tattoo in European and American History, Londres, Reaktion Books, 2000. Amelia K. Osterud, The Tattooed Lady. A History, Lanham, Boulder, New York et Londres, Taylor Trade Publishing, 2014. Christelle Taraud (dir.), « Femmes orientales dans la carte postale coloniale », Musea. Musée virtuel sur l’histoire des femmes et du genre, sans date.