The 1785 edition of the Royal Academy summer exhibition left its visitors perplexed. A contemporary critic wrote that it lacked in historical paintings. They did not comment on the intriguing portrait displayed in the antechamber, though. ‘Poedua, Daughter of Oree, chief of Ulaietea, One of the Society Isles’ was signed by John Webber, the artist who travelled with Captain Cook during his third exploratory voyage in the Pacific (1776–1779). This portrait of a young, tattooed woman of the Society Isles is connected to a curious case of kidnapping.

There are three versions of this painting in existence. The first is located at the National Maritime Museum in London: being the most detailed, it probably is the one that was exhibited in 1785. Another is a part of the Nan Kivell Collection at the National Library of Australia. The last one is held in a private collection. Poetua’s tattooed body is well known amongst scholars: her portrait was the first painting of a Polynesian woman to reach a European audience. Poetua’s name (Te Poe Tua) means ‘the pearl of the ocean’. According to art historian Jeanette Hoorn, she was originally from Bora-Bora, where her father Oreo was a chief. She happened to be on the island of Raiatea during a visit from Captain Cook in August 1777. As a matter of fact, Poetua and Captain Cook knew each other pretty well. He had met her during his second exploratory voyage in the Pacific and had established trusting relationships with her family. But the August 1777 excursion found the seafarer at his wit’s end. Exhausted by his trips, he committed several atrocities on the island: he set fire to houses when a goat was stolen from the European’s, cut out a man’s ears in retaliation from a theft… It all culminated one day, when Poetua and her family were invited on the ship and then locked down. If the island’s inhabitants were to fail at bringing back two deserters, the captives would be taken to Europe against their will.

This was the improbable context in which John Webber started to paint Poetua. The British-Swiss artist was used to executing quick sketches in order to turn them into proper portraits in his London studio: his role on the James Cook expedition was to document the customs and landscapes they encountered. So he drew Poetua during her captivity and later painted a small, now lost portrait that served as a basis to the three known ones. Since John Webber’s sketch and first painting are now lost, it is impossible to verify how Poetua’s image changed from one drawing to the next. Because Poetua’s portrait should be taken with a grain of salt, when it comes to accuracy. First, it relies heavily on the artistic conventions of the time. Poetua displays the attitude of “Venus Pudica”, a then-popular ideal of female beauty through modesty and purity. It echoes to the then-common belief that Polynesian people remained into a sort of ‘state of nature’ where man is good, innocent, and pure. In such literary depictions, tattooing was often depicted as a primitive way to ornate one’s body, akin to embroidering the skin. However, this idealisation wasn’t deprived of eroticism. Peotua appears half-naked and passive; nothing reveals the sinister conditions in which this portrait was sketched. Polynesian women – and especially women from Tahiti and its nearby islands – were then viewed as sexually promiscuous. It was a gross overinterpretation inherited from Bougainville’s travels. At the time, Poetua’s beauty was the topic of many questionable jokes regarding her captivity, and whether she was secretly happy about it or not… Both biases explain the young woman’s surprisingly relaxed pose: it was the painter’s way to meet his public’s expectation of what a Polynesian woman should look like.

And then there’s her arm. It is put front and centre, right before her belly, to highlight her tattoos; though it might also be because she was then pregnant. In the late 18th century, tattooing wasn’t a new concept to the Europeans who travelled to Polynesia. What was surprising to them, though, was how common and peculiar the practice was there. Therefore, tattooing was often portrayed in drawings and paintings. The most famous example might be the portrait Joshua Reynolds painted of Omai, a Raiateia native. He was part of James Cook’s second travel and worked as an interpreter during the third one. He was actually brought back to his native island right before Cook crossed paths with Poetua again. In Reynold’s painting, Omai displays his tattooed hands and forearms in a way that resembles Poetua’s position; even the tattoos are similar in nature. But tattooed women spark curiosity in a very specific way. Queen Purea, who Samuel Wallis encountered in 1767 and James Cook in 1769, was the topic of many erotic and humoristic stories, inspired by her love life and tattooed buttocks. Tattooed skin, when put on display, meant exoticism, eroticism, and strangeness all at once. At least, it did to European observers whose main experiences of tattooing was on the body of men, and especially of sailors. Poetua’s captivity lasted four days, from the 25th of November 1777 to the 29th. She died two years later. She was survived by the three versions of this portrait, in which she is eternally displayed as a Polynesian woman rooted in fantasy. But she accidentally became a testimony to one of the many aspects of tattooing in the Pacific islands.

Sources des illustrations

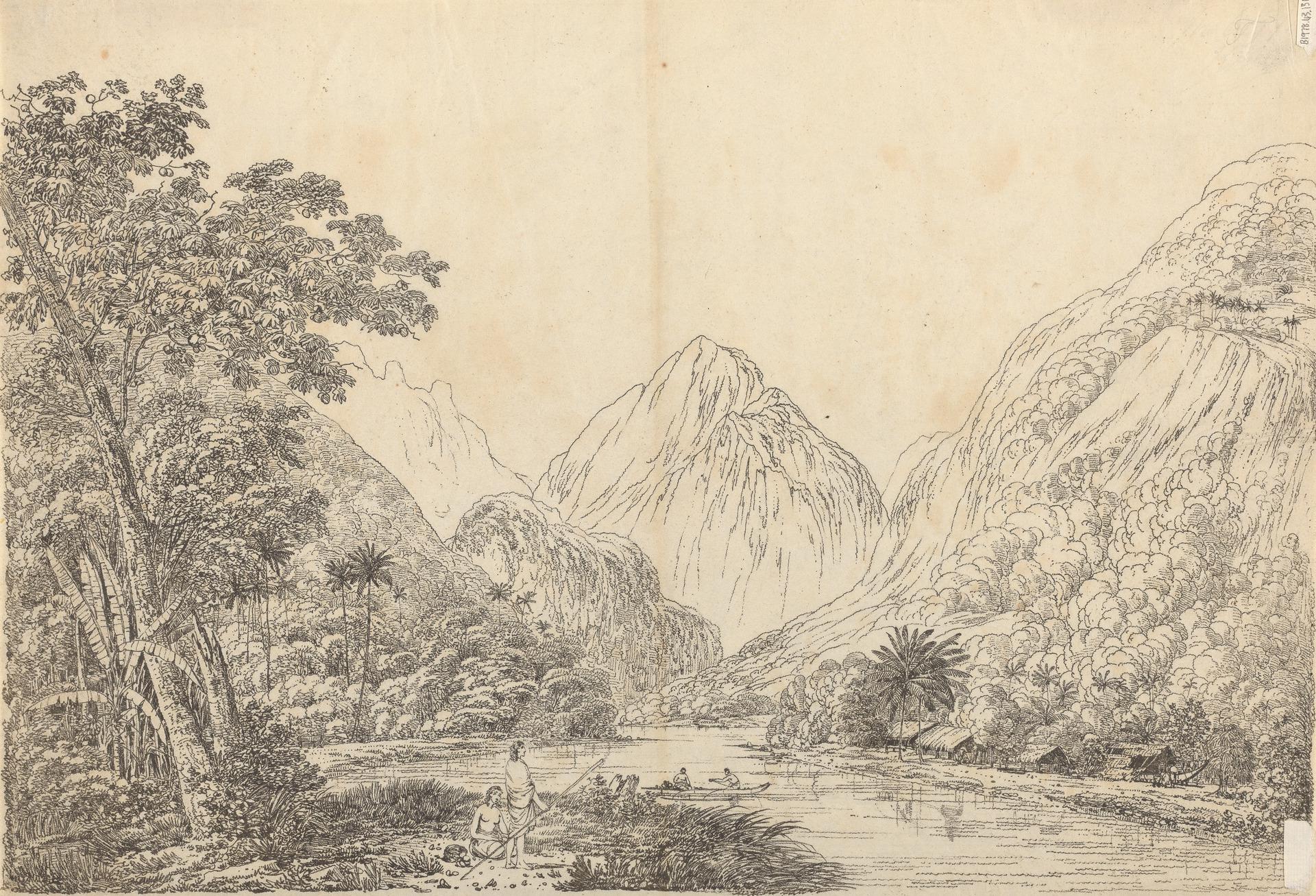

John Webber, ‘Poedua, the Daughter of Orio’, 1777, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, BHC2957 (Wikimedia – Domaine public). John Webber, ‘View of Oheitepeha Bay, Otaheite’, Yale Center for British Art, 1791, B1978.43.1316 (Wikimedia – Domaine public). Joshua Reynolds, ‘Portrait of Omai, a South Sea Islander who travelled to England with the second expedition of Captain Cook’, 1775–1776, Castle Howard, Yorkshire (Wikimedia – Domaine public). Pour aller plus loin “‘Poedua, the Daughter of Orio’ (b. circa 1758 – d. before 1788)”, Royal Museums Greenwich. Harriet Guest, ‘Curiously Marked. Tattooing and Gender Difference in Eighteenth-century British Perceptions of the South Pacific,’ in Jane Caplan (dir.), Written on the Body. The Tattoo in European and America History, Londres, Reaktion Books, 2000, pp. 83–101. Matthew Hargraves, ‘1785. London versus Rome,’ The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition: A Chronicle, 1769–2018. Jeanette Hoorn, ‘Captivity and humanist art history. The Case of Poedua,’ Third Text, n° 42, 1998, pp. 47–56. A Marata, Tamaira, ‘From Dusk to Full Tusk: Reimagining the “Dusky Maiden” through the Visual Arts’, The Contemporary Pacific, vol. 22, n° 1, 2010, pp. 1–35. Nicholas Thomas, Océaniens. Histoire du Pacifique à l’Âge des Empires, Toulouse, Anacharsis, 2020.