‘This eighteen-year-old girl is a gang leader’ published French newspaper Police Magazine on the 5th of July 1931. Right next to the article is an ad aimed at teaching us that ‘you can only wear a swimsuit if you have a beautiful chest’. Nevertheless, Dorcas Bacon catches the eye. On the accompanying photograph, her sleeves are rolled up to reveal two tattooed forearms. On the left one: a dagger and a skull, decorated with the words ‘Death Before Dishonor’ on a ribbon. On the right one: a snake and the words ‘The Godless Girl’.

We won’t learn much more about Dorcas Bacon from the French press. We know that she had a lot of ‘Roméos’, that she was from Detroit, that she apparently shot at a man twice, and was already in prison… and that’s about it. ‘W. W.,’ the enigmatic author of the paper, seems less interested in her biography than in her picturesque appearance. Tattoos, ‘hands fit for a strangler’, a ‘virile’ face: the portrait is biased to fit the exotic way French people used to imagine the American criminal class. ‘An extraordinary example of the ruthless “lunatics” we often meet among the American underworld!’ wrote W. W. Case closed. During the interwar period, newspapers catered to a renewed fascination from their readers towards crimes and those who commit them. Magazines like Détective or Police Magazine were aimed at chronicling the most extraordinary cases of the times. They were especially fascinated by the American ‘gangster’, whose myth circulated through novels and movies. Though they pretended to produce reliable news, they weren’t above some level of sensationalism… and were known to sometimes cut corners. I had to rummage into American newspaper archives to find more information about Dorcas Bacon. The Detroit Free Press published an article about her on the 23rd of March, while she was in a women’s detention home. Dorcas actually committed a series of hold-ups which culminated with her arrest on the 21st. There again, journalist Dorothy Williams does not try to hide her fascination for Dorcas’s appearance and tattoos. ‘Godless Girl’ is apparently the young woman’s motto and she had it tattooed at sixteen. However, this is where the similarities with Police Magazine end. It turns out that Dorcas Bacon is not a gang leader. Before her arrest, she was employed as a maid in a Grosse Pointe home, near Detroit. She claims that she attacked a drug store, perhaps two (some newspapers hint at another location) and a restaurant to help her aunt, who needed money.

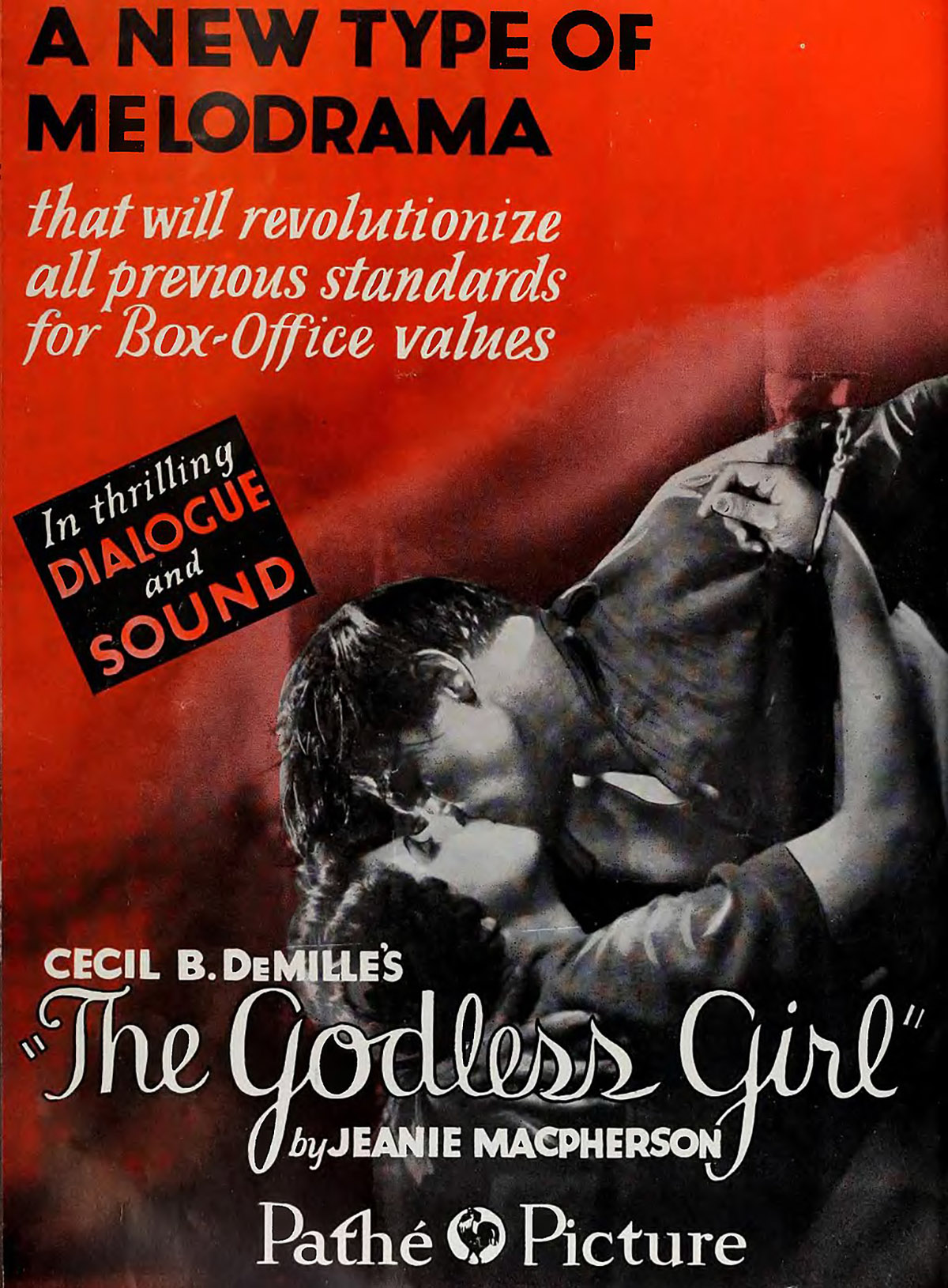

Not quite a gang leader then, though she did have an accomplice: a man who agreed to drive her around. However, Dorcas Bacon remains a fascinating character. She announces her intention to plead guilty, claims that she was ready to kill if necessary. It turns out that the two shots she fired were actually aimed at a clerk in one of the drug stores. Born in Memphis, Tennessee, she moved with her parents to Cadillac, Michigan, when she was five. Then, she lived with her aunt for a while. On Saturday the 4th of April, she was sentenced to serve from two to ten years in the Detroit house of correction. And her appearance keeps on fascinating. Dorcas’s mugshots appear in countless newspapers. They are usually accompanied by descriptions of her tattoos, and very little information about the actual case. Police Magazine probably gathered its intel from one of those short articles. In black and white, sometimes with a cocky smile, Dorcas Bacon seems to defy the police and the reader. On the 31st of March, the Lincoln Star published one of such articles, titled ‘Godless Girl’. Her tattoo thus became the summary of her very personality, her nickname as a delinquent. Perhaps she found inspiration for this tattoo in a Cecil B. De Mille’s movie of the same name. It came out between 1928, first as a silent feature, then as a talkie. The dates do match, even though this odd drama about an atheist teenager, a murder and a juvenile prison was a complete box office disaster. Was Dorcas one of the few people who bothered watching it? Was she inspired by an ad? We can’t know for sure.

There’s an epilogue to Dorcas’s story. In 1936, the Philadelphia Inquirer published a short retrospective on her crimes and trial. The article is highly romanticised, and the five-year gap probably does not help its accuracy. It contains no mention of Dorcas trying to help her aunt. The only highlighted motive is misandry: ‘I hate men’ was apparently one of her first things she told the police. She even provided a reason for that fierce hatred: while she was training as a nurse, a patient apparently tried to assault her. The article does remain questionable, though, as it even manages to get the verdict wrong… But it, too, lingers on her ‘Godless Girl’ tattoo. ‘God’s a man. I hate Him too!’ she supposedly claimed to justify it. Quite the declaration, for a tale aimed at shocking the pious people of the USA... Sources Dorothy Williams, « Tattooed Girl Bandit Caught », Detroit Free Press, 23 mars 1931. « Godless Girl », Lincoln Star, 31 mars 1931. « Dorcas Bacon Gets Two to Ten Years », Detroit Free Press, 5 avril 1931. W. W., « Une jeune fille de dix-huit ans chef de bande », Police Magazine, 32, 5 juillet 1931. Arthur Kent, « Calling All Cars! », The Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 octobre 1936. Sources des illustrations « Une jeune fille de dix-huit ans chef de bande », Police Magazine, 32, 5 juillet 1931 (collection personnelle). A.P. Photo, « Godless Girl », Lincoln Star, 31 mars 1931, via archive.org (domaine public). Affiche de Cecil B. De Mille, « The Godless Girl », 1928-1929, via Wikimédia (domaine public). Pour aller plus loin « The Godless Girl », The Hope Chest. Bad news from the past, 10 mars 2009 (URL : https://mrparallel.wordpress.com/2009/03/10/the-godless-girl/, page consultée le 22 décembre 2022). Nicolas Picard, « Une autre forme d'“apothéose infâme”. Médias et public face à la célébrité criminelle (années 1930-1950) », Hypothèses, 15/1, 2012, p. 145-155.